Artless art, planless plan . . . The great overarching quality of buncheong is its vitality and its mixture of grandeur and roughness.

—KO Yuseop (1905–1944)

Understanding Buncheong Ceramics and Their History

Korean buncheong ceramics have a fascinating history, though their production in Korea spanned a relatively short period of fewer than two hundred years, from the end of the fourteenth century to the late sixteenth century. The term “buncheong” (an abbreviation of bunjang hoecheong sagi) was coined by KO Yuseop (1905–1944), an early-twentieth-century Korean art historian, and it refers to “white-slipped stoneware.” Bun 분 means “powder” and cheong 청 can be translated as green or blue. (Celadon in Korean is cheongja, and here cheong indicates celadon stoneware.) Buncheong ceramics have the distinctive characteristic of being covered with white slip (a mixture of white clay and water). Interestingly, historical written records, up until the twentieth century, merely referred to works in this particular style as vessels or ceramics.

Buncheong wares are intricately linked to the establishment of the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897), an era characterized by a shift in state beliefs and a desire for new artistic expressions. Unlike the preceding Goryeo dynasty (918–1392), which had embraced Buddhism as its state religion, the Joseon dynasty adopted Confucianism as its guiding belief system. This significant ideological transformation influenced the aesthetics of the time, leading to a preference for minimalism, elegance, and a reduction of elaborate adornments in artworks. As a result, the once highly revered Goryeo-dynasty celadon ceramics and Buddhist paintings, known for their delicate techniques, opulent materials, and intricate surface decorations, gradually fell out of favor in this new cultural climate.

Furthermore, at the end of the Goryeo dynasty, the country faced the ravages of numerous Japanese pirate invasions along its coastal regions. These devastating incursions resulted in the destruction of major celadon kilns, further aggravating the decline of celadon production. Consequently, many skilled potters were compelled to leave the traditional celadon kiln areas and move to new locations in search of suitable resources for ceramic production, including clay, wood, and appropriate slopes to build kilns.

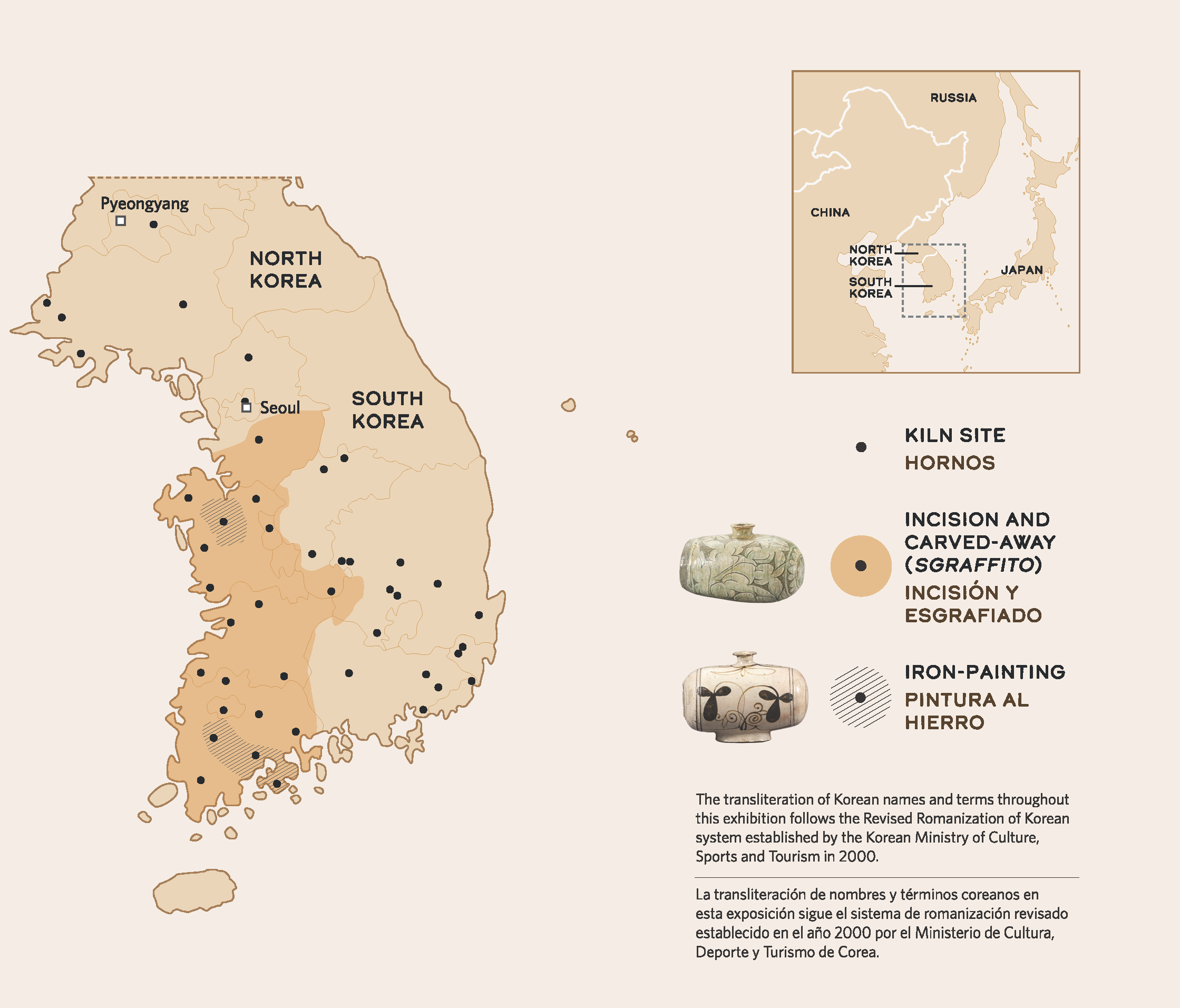

Unfortunately, their endeavors to locate the high-quality, refined clay like that used for celadons often proved unsuccessful. In response to this challenge, the potters devised a creative solution by applying a white slip to cover up the rough surface of their ceramics. This innovation opened up exciting possibilities for experimentation with various surface decoration techniques, such as inlay, stamping, incising, carved-away (sgraffito), iron painting, brushed white slip, and dipped white slip, resulting in a rich and diverse array of designs. Buncheong wares, in contrast to celadons, which had been primarily produced in specific kilns for particular users and markets, were created all across the Korean peninsula and catered to various social classes (fig. 1). They served a wide range of functions, from being used as royal ritual vessels to everyday household items.

Notably, the influence of buncheong wares extended beyond Korea’s borders, leaving in particular a significant mark on Japanese ceramics, especially following the Japanese invasions in the late sixteenth century. These invasions, often referred to as the “ceramic wars,” resulted in the forced migration of many Korean potters to Japan. While buncheong wares left a lasting impact on Japanese ceramics, they regrettably faced a decline in production and popularity within their home country due to changing artistic trends and evolving preferences for whiteware porcelain.

“Perfectly Imperfect” Buncheong Ceramics Viewed from the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

Whimsical, rustic, audacious, naturalistic, impromptu, direct, and contemporary—these expressions have been associated with Korean buncheong ceramics, which have captivated artists and theorists throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. During the twentieth century, Korean artists and theorists grappled with the interplay of modernization and tradition while seeking to define the essence of Korean-ness. Many artists turned their gaze toward the genuine, fresh, and fundamental qualities exhibited by the buncheong potters from the past, using them as an inspiration to create more captivating and relevant modern artistic concepts.

Korean art historians and connoisseurs have come to recognize the immense creative potential of buncheong ceramics in both modern and contemporary contexts. Art historian and former director of the National Museum of Korea CHOI Sun-u (1916–1984) noted that the essence of buncheong is that it contains “simplicity and naivete . . . The beauty of fresh, broad-minded wildness.”1 As for the Korean-ness in buncheong, KIM Won-Yong (1922–1993), a notable professor of Korean archaeology and art history, pointed out, “Buncheong is a totally new genre of ceramic art in terms of the total effect of its techniques and aesthetics. It is quintessentially Korean.”2 Professor and eminent Korean art historian AHN Hwi-joon (born 1940) goes further: “Buncheong’s excellence lies in its immediacy and improvisation of expression. There is no other country where you can find such potters expressing their bold ideas . . . Buncheong is the ceramic that is the most essentially Korean.”3

While buncheong production ceased in Korea during the sixteenth century, the Japanese have remained captivated by the allure of imperfection inherent in buncheong wares. They have consistently found inspiration in the robust sensuality, playful design, and striking minimalism that characterize traditional Korean buncheong ceramics. Notably, YANAGI Sōetsu (1889–1961), a prominent Japanese art theorist and collector, highly praised the aesthetics of buncheong, particularly celebrating its perfectly imperfect qualities:

Korean [buncheong] work is but an uneventful, natural outcome of the people’s state of mind, free from dualistic, man-made rules. They make their asymmetrical lathe work not because they regard asymmetrical form as beautiful or symmetrical as ugly, but because they make everything without such polarized conceptions . . . Here, deeply buried, is the mystery of the endless beauty of Korean wares. They just make what they make without any pretension.4

(For more on the influences of buncheong ceramics on modern and contemporary art in Korea, refer to “Creativity and Heritage in Contemporary Korean Craftsmanship”.)

The exhibition Perfectly Imperfect: Korean Buncheong Ceramics at the Denver Art Museum showcases the continuity of the buncheong tradition in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, featuring three representative artists. Among them, YOON Kwang-cho (born 1946) stands out as a pioneering figure in the revival of the tradition. From as early as 1970, when Yoon decided to study buncheong idioms, he has continually explored a dialogue between the traditional and the contemporary (fig. 2). Beginning in the 1990s, Yoon took a bold artistic turn by abandoning the potter’s wheel in favor of hand-shaped slabs. His work became more sculptural, with his buncheong ceramics taking on rectangular shapes with unfinished-looking edges.

Like Yoon, LEE Kang Hyo (born 1961) is also deeply inspired by the lines and forms found in the Korean natural landscape. For Lee, buncheong ware bodies serve as a canvas for representing mountains or the earth, while white slip takes on the role of water or clouds. But Lee’s artistic exploration goes beyond mere representation; he delves into the realm of performance art as an integral part of his creative process. This includes techniques such as punching wet clay, throwing white slip, and tapping on the slipped buncheong surface. These dynamic and expressive methods infuse his works with a sense of liveliness, a connection to the natural world, and an inherent spontaneity that aligns perfectly with the concept of “perfectly imperfect.”

The artistic expression of HUH Sangwook (born 1970) revolves around captivating decorative motifs, with particular inspiration from traditional East Asian paintings’ plantain leaf and peony imagery. Huh also skillfully transforms the traditional buncheong ware forms into modern renditions. His flask-shaped bottles are slenderer and more substantial than traditional bottles, while his barrel-shaped bottles adopt more angular and dynamic forms, pushing the boundaries of conventional design. Huh’s ingenuity shines through with his own innovation of adding silver paint to the surfaces of his pieces before glazing and final firing. Over time, Huh’s buncheong ware develops its own fascinating history, as the silver elements undergo changes in color, even after completed.

Hyang Jin CHO, a Korean American ceramist working in Colorado, creates her works as a means of expressing her emotions and viewpoints concerning the events unfolding around her. Her Urn for Commemorating April 16th, part of the series Inevitable Coincidence, stands as a testament to her process of grieving the tragic loss of 304 lives when the Sewol ferry sank in 2014 (fig. 3). The forms in this series are based on the placenta jars of the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897), similar to Lidded Placenta Jar with Floral Motif and Cover with Lotus Petal Motif from the Placenta Chamber of Prince Gyeyang (1427–1464) (fig. 4, refer to “Buncheong Ceramics before Birth” in this publication). By drawing from the rich heritage of buncheong wares, these artists seek to infuse their works with a sense of timelessness and cultural depth that transcends the boundaries of history and resonates with contemporary audiences.

Buncheong Ceramics in Exhibitions

Until the 1990s, the study of buncheong ceramics in Korea was still in its early stages, despite ongoing excavations of buncheong kiln sites since the early twentieth century, which continuously yielded valuable new data published in excavation reports. However, a significant milestone was achieved with two groundbreaking special exhibitions, Masterpieces of Buncheong Ceramics I and II. These exhibitions took place in 1993 and 2001 at the Ho-Am Gallery in Seoul and featured an impressive display of 250 and 103 objects, respectively. Both exhibitions, organized by the Ho-Am Art Museum and Samsung Foundation of Culture, played a pivotal role in shedding light on the characteristics and aesthetic values of Korean buncheong ceramics. The second exhibition also juxtaposed the traditional ceramics with some modern buncheong works, such as those of Yoon Kwang-cho.5

Since the Ho-Am Gallery’s exhibitions, there has been a notable increase in the number of unearthed buncheong objects and scholarly publications, leading to more focused and specialized buncheong exhibitions in Korea. One such noteworthy exhibition, Buncheong Ware from Mt. Gyeryong Kilns, was held at the National Museum of Korea in 2009. This exhibition was centered around unearthed buncheong works from specific kilns in the Gyeryong mountain region. (For further details on the Gyeryong buncheong ceramics, refer to “Rustic Elegance from Mount Gyeryong: Buncheong Surface Design in Iron Painting” in this publication.) In 2022, the National Museum of Korea held another significant exhibition, The Subtle Charms: White Slip Brushing and Coating. This exhibition in the museum’s newly installed ceramics galleries specifically highlighted two surface design techniques used in buncheong ware.

Beyond Korea, the first major exhibition of buncheong was Poetry in Clay: Korean Buncheong Ceramics from Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco in 2011.6 The exhibition featured more than sixty traditional buncheong ceramics, offering a comprehensive exploration of the various techniques and motifs as well as buncheong’s influences on Japanese ceramics and contemporary art.

It is significant that, more than a decade after the first major buncheong exhibition in the United States, the Denver Art Museum and the National Museum of Korea now present Perfectly Imperfect: Korean Buncheong Ceramics (December 3, 2023–December 7, 2025) in Denver, Colorado. This exhibition features more than sixty objects, including traditional buncheong ceramics as well as modern and contemporary artworks, delving deeper into the profound meaning and diverse expressions found in buncheong ceramics. The thirty-three traditional buncheong wares in the exhibition are from the collection of the National Museum of Korea, which recently came to hold the largest museum collection of buncheong thanks to a significant donation from the Samsung family in 2021.7 Through the display of sherds and deformed buncheong wares, the exhibition also offers a revealing insight into the meticulous and challenging processes involved in producing buncheong ceramics. The Perfectly Imperfect exhibition demonstrates the variety of buncheong motifs, functions, and techniques; the rigorous procedure of making traditional buncheong ceramics; the Korean-ness in buncheong designs and the potters’ ideas; as well as the appeal and relevance of buncheong to twenty-first-century artists and viewers. The exhibition offers a captivating window into the world of Korean buncheong ceramics, fostering a deeper appreciation for this unique and culturally significant art form among international audiences.

Hyonjeong Kim Han (HKH)

Joseph de Heer Curator of Arts of

Asia

Notes

-

Choi Sun-u, Choi Sun-u jeonjip [Compilations of Choi Sun-u Writings] (Seoul: Hakgojae, 1992), Vol. 1, 5, and Vol. 4, 398.↑︎

-

Kim Wonyong and Ahn Hwi-joon, Hanguk misul-eu yeoksa [History of Korean Art] (Seoul: Sigongsa, 2005), 574–75.↑︎

-

Ahn Hwi-joon and Lee Kwangpyo, Hanguk misul-eu mi [The Beauty of Korean Art] (Seoul; Hyohyung, 2008), 254–55.↑︎

-

Yanagi Sōetsu, “Notes on Joseon Period Kilns,” in Joseon-eul saenggakhanda [Thinking of Joseon] (Seoul: Hakgojae, 1996), 222.↑︎

-

Ho-Am Gallery, Buncheongsagi myongpumjeon I &II [Masterpieces of Buncheong Ceramics I &II] (Seoul: Ho-Am Gallery, 1993 and 2001).↑︎

-

Soyoung Lee and Seung-chang Jeon, Poetry in Clay: Korean Buncheong Ceramics from Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; San Francisco: Asian Art Museum; New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011).↑︎

-

Out of thirty-three traditional buncheong wares in the exhibition, twenty-one works were donated by the Samsung family in honor of the deceased chairman of the Samsung Group, Kun-hee Lee.↑︎