In 1411, an unprecedented event shook the court of the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897) in Korea when King Taejong (1367–1422: reigned 1400–22) was presented with a colossal foreign creature—an elephant from Indonesia—as tribute from Japan.1 The initial awe and fascination soon gave way to frustration, as the massive animal proved to be a source of trouble, causing the deaths of several people and consuming a vast amount of stock feed. As the annoyance grew, the elephant was soon relocated to an island and then to various cities in the southern part of Korea.

In spite of this troubling event, vessels in the shape of elephants held significant importance in proper Confucian rituals at the Joseon court (fig. 1). Drawing from the teachings of the Book of Rites, a Confucian treatise created in the eleventh century in China, these elephant-shaped vessels were primarily utilized to hold wine during summer ceremonies or rituals. This association with summer stemmed from the belief that elephants, the largest animals known at that time, hailed from regions with hot weather.2

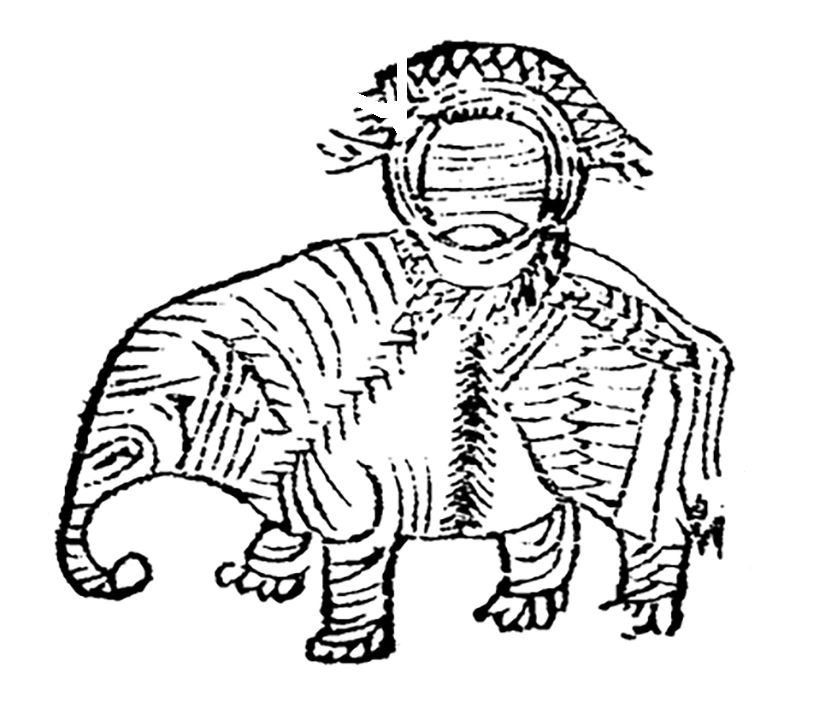

In 1474, Joseon Confucian official-scholars compiled The Explanatory Illustrations of Confucius Ritual Vessels, a comprehensive account detailing the regulations and particulars of official ritual vessels, which included the elephant-shaped vessel (fig. 2). According to this book, each vessel held a designated position on the ritual table, determined by the specific food it contained and the symbolic significance of the food’s colors. Typically, the elephant-shaped vessel would be positioned in the front row, closest to the worshippers. It is noteworthy that this particular vessel was exclusively reserved for official ceremonies and strictly prohibited from being used in family or private rituals.

For royal rituals at the Joseon court, bronze was favored for crafting ceremonial vessels (fig. 3). However, in the early years of the Joseon dynasty, a shortage of bronze led to a state mandate aimed at reducing its usage.3 As a result, ritual vessels began to be produced in buncheong ceramics. The elephant-shaped vessel featured in the Perfectly Imperfect exhibition exemplifies this material shift. Although based on the same elephant shape as the bronze vessels, this buncheong ceramic rendition carries a more lighthearted and humorous tone.

Adding to its charm, an abstract depiction of a tortoise is incised on the back of the vessel body on both sides. In traditional East Asian society, tortoises symbolized longevity, much like elephants, which further enhances the vessel’s significance. It raises the interesting question of whether the potter spontaneously added the tortoise or if the intention was to incorporate two animals—one large (elephant) and one small (tortoise). But whose longevity was the vessel for? Was it for the worshippers or the dead?

HKH

Notes

-

The Annals of King Taejong 21, in The Annals of the Joseon Dynasty [in Korean] (1393): 10b, https://sillok.history.go.kr/popup/viewer.do?id=kca_11102022_002&type=view&reSearchWords=코끼리&reSearchWords_ime=코끼리.↑︎

-

“Vessel in the Shape of Cow” and “Vessel in the Shape of Elephant,” in The Explanatory Illustrations of Confucius Ritual Vessels [in Korean] (1474), https://sillok.history.go.kr/popup/viewer.do?id=kda_20002008_017&type=view&reSearchWords=&reSearchWords_ime=.↑︎

-

Even in the previous Goryeo dynasty, in 1391, King Gongyang received a formal appeal from an official, who stated, “Glass and bronze vessels are not easily made in this country. I am requesting that the use of bronze and metal wares should be prohibited. Please revise our customs so that only ceramic and wooden wares can be used.” [History of Goryeo, gwon 35] Hyonjeong Kim Han, “More than a Bowl: Buncheong Ceramics with Inscriptions,” Lotus Leaf 14, no. 1 (Fall 2011): 1.↑︎