Throughout Korean history, a baby’s placenta and umbilical cord (tae) have been believed to profoundly influence their future life. Among the customs associated with this belief was the exclusive jangtae practice (burying a placenta and umbilical cord), reserved solely for the Joseon royal family. During this ritual, the placenta and umbilical cord of a royal baby were ceremoniously buried in an auspicious location guided by the principles of East Asian geomancy. The significance attributed to these extended beyond the royal child’s personal well-being and longevity. It was also thought to impact the prosperity of future generations within the royal family and even the welfare of the entire nation. As a result, protective structures were erected to mark this special location, ensuring its sanctity and safeguarding the site’s importance.

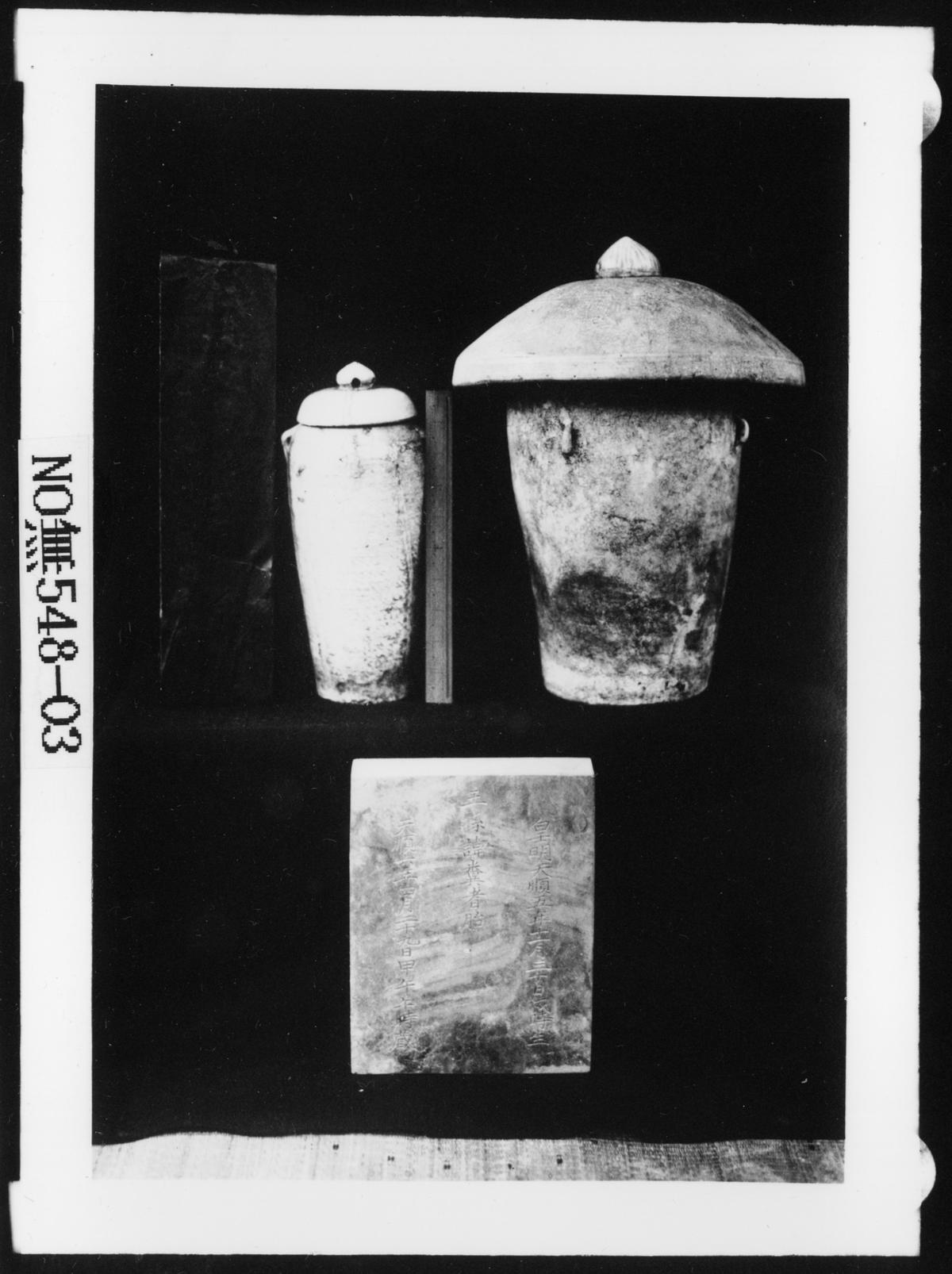

The Lidded Placenta Jar with Floral Motif and Cover with Lotus Petal Motif of Prince Gyeyang (1427–1464), in Perfectly Imperfect: Korean Buncheong Ceramics, demonstrates this historical tradition. It originates from the placenta chamber of Prince Gyeyang, the eighth son of the renowned King Sejong (1397–1450: reigned 1418–50). Prince Gyeyang actively supported his brother King Sejo’s (1417–1468: reigned 1455–1468) coup against his nephew King Danjong (1441–1457: reigned 1452–1455). Prince Gyeyang’s placenta vessels were discovered along with a stone tablet indicating that he was born in 1427 and that his placenta was buried in the chamber in 1439 (fig. 1).1 This lidded jar was used to store the placenta and umbilical cord collected at his birth. Like other buncheong wares made for the Joseon royal court, the jar features the delicate motif of chrysanthemum floral in the stamping technique. The cover has a knob and is adorned with four tiers of patterns, including a lotus petal motif with an inlaid technique. This unique type of large cover was found exclusively in the placenta chamber site of princes of King Sejong’s lineage in Seongju, North Gyeongsang province (figs. 2 and 3). This collective burial site is for the placentas of nineteen princes.2

After the royal birth, a ritual of purifying the placenta and umbilical cord took place on the third or seventh day. This involved washing them multiple times with clean water, followed by cleansing with fragrant liquor. Once purified, the placenta was carefully placed in a pottery jar, which was then sealed. Crucial information such as the date of birth, the name of the person who led this ritual, and the name of the baby were written on paper and attached to the jar.3

Jars used to store the royal placentas were of the highest quality during that period. As a result, the placenta chambers, which were highly secured and strictly managed during the Joseon period, eventually became a target for looting in the early twentieth century. During the Japanese colonial period (1910–45), the colonial government utilized administrative issues as a pretext to dismantle the connections between the Joseon royal family and the local communities (fig. 4). They randomly collected placenta jars from different locations across the country and centralized them into one location. Unfortunately, certain placenta jars, particularly those with artistic value, found their way into private or public museums, as well as art markets. As a result, many times, these objects lost their original context, which illustrates a lamentable aspect of twentieth-century Korean cultural history.

JYP

Notes

-

The stone tablet for Prince Gyeyang’s placenta chamber states, “Buried on the 24th day of the 5th month in 1439, Prince Gyeyang’s umbilical cord and placenta, who was born between 1 and 3 am on the 12th day of the 8th month in 1427.” Author’s translation, based on the transcription of the tablet in The National Museum of Korea: The Lee Kun-Hee Collection at the National Museum of Korea, Vol. 7: Buncheong Ware (Seoul: The National Museum of Korea, 2022), 302.↑︎

-

Eighteen sons and one grandson of King Sejong. The eldest son, who became King Munjong (1414-1452: reigned 1450-1452) was not included.↑︎

-

SHIN Myeong-ho, Joseon wangsil-ui uirye-wa saenghwal, gungjung munhwa [Rituals, life, and palace culture of the Joseon royal court] (Seoul: Dolbegae, 2002), 303.↑︎