The Imjin Wars (1592–98), known as the “ceramic wars,” had a profound impact on ceramic production in Korea during the 1500s. The invasions of Japan devastated the southern part of the Korean peninsula and captured numerous potters, disrupting the production of Korean pottery. Even royal ceramic production took a considerable time to recover, leading to certain arguments that the buncheong tradition was entirely lost.

This event is connected to the emergence of the wabi-cha culture in Japan from the 1500s onwards. This simple and tranquil tea ceremony culture became popular among samurai warriors. The tea ceremony aimed to achieve an aesthetic and state of mind drawn from certain principles of Zen Buddhism, favoring a rustic and nature-friendly atmosphere. This resonated with the perfectly imperfect aesthetics of Korean ceramics such as buncheong ware and low-fired white ware (figs. 1 and 2). Korean tea bowls, like koraijawan (Goryeo tea bowl) or idojawan (well tea bowl) (fig. 3), replaced the previously preferred colorful Chinese tea bowls, such as tenmokujawan (heaven’s eye tea bowl), representing a shift in taste.

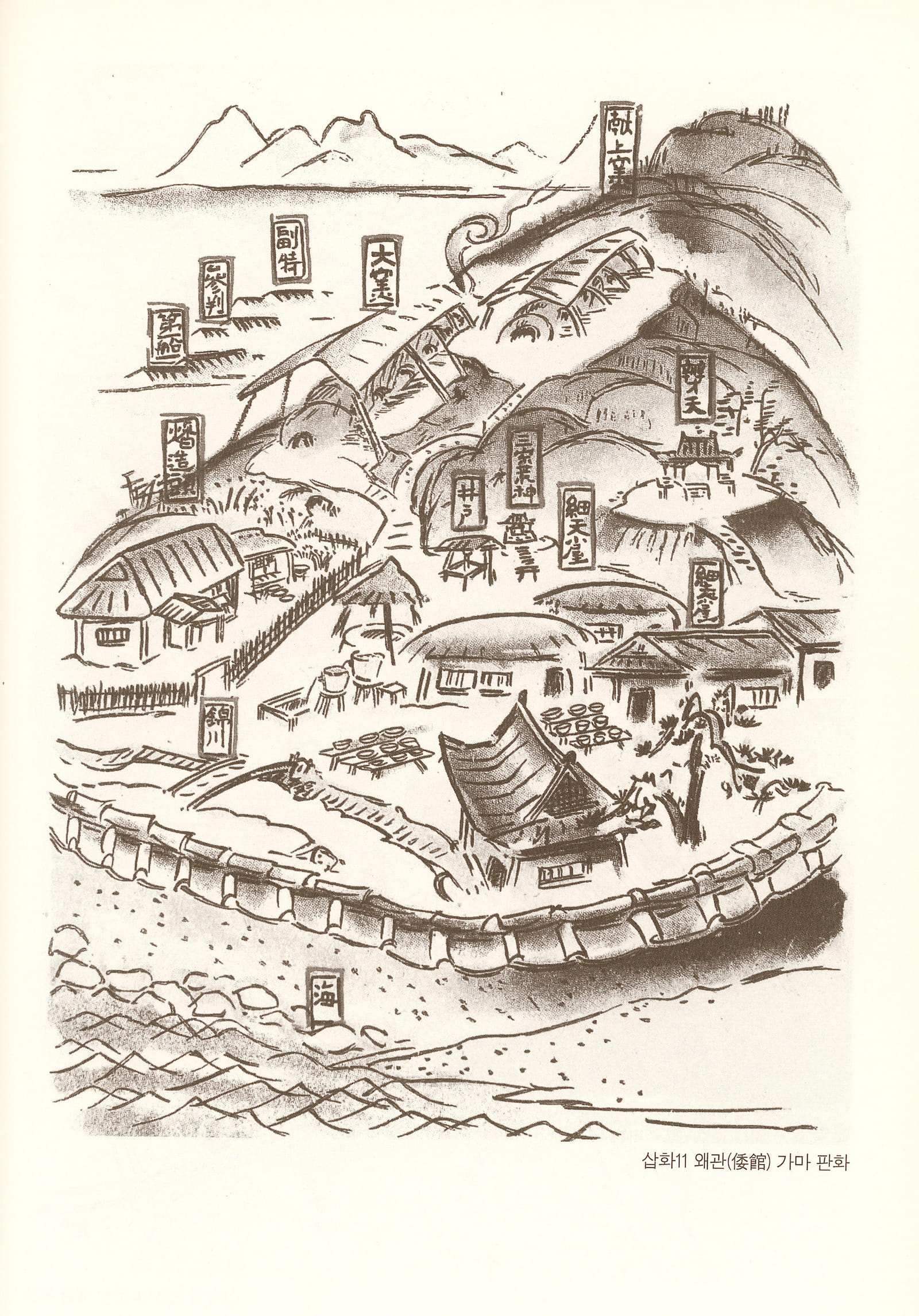

By 1600, the kidnapped potters had brought a Joseon vein to Japanese ceramic production and established a new tradition of Japanese pottery, especially on the island of Kyushu, in Japan. At the same time, potters in the southern part of the Korean peninsula, notably Gyeongsang province, continued to produce significant quantities of buncheong ware for export to Japan. After the two countries restored diplomatic relations in 1639, the Tsushima clan in Japan requested to install kilns like those from Busan, Korea, and buncheong-style tea bowls, known as gohonjawan (model-style tea bowl), were made to Japanese specifications for more than seventy years (fig. 4). These ceramic works for Japan differed significantly from the prevailing tastes in contemporary Korean ceramics, such as whiteware, which featured a clear white color and moderate decoration.

During the early twentieth century, YANAGI Sōetsu (1889–1961), the Japanese art theorist and initiator of the Mingei (Folk Art) movement, found deep admiration for buncheong ware, called Mishima ware in Japan at that time. While viewing the renowned Kizaemon O Ido tea bowl, made in Korea in the 1500s, he expressed, “It is a splendid tea bowl, yet how it is so ordinary?”1 He was drawn to the allure and significance of a plain tea bowl from the Joseon dynasty, originally utilized by the less wealthy, appreciating its unembellished, authentic attributes designed for everyday functionality, and he commended these unpretentious qualities as worthy of admiration.

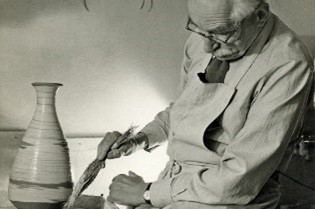

Bernard Leach (1887–1979), the British ceramic artist and colleague of Yanagi’s, criticized British pottery such as Wedgwood, labeling it “unnatural, useless, and false” (fig. 5). In contrast, he praised Eastern pottery, Korean ceramics included, for their remarkable ability to harmonize spiritual and practical requirements.2 Leach was particularly inspired by buncheong’s brushed slip technique and incorporated its tool, a “miniature garden broom made of the grain ends of rice straw,” commonly employed by Joseon potters for white slip decorative work, into his own creations, which significantly influenced contemporary ceramic art.3 Despite the political turbulence experienced by Korea in the first half of the twentieth century, its ceramic craft gained cultural admiration from various international theorists and artists.

JYP